So, who’s up for some bloodwork? Venipuncture, anyone? Finger prick, maybe? No..? Oh… Well, ok then. I’ll carry on. I know it may sound a bit crazy, but as a PT, I actually do some (very) minor blood work. I’m not trained as a nurse or phlebotomist or anything like that. Nope. Just some on-the-job-training on doing PT/INRs.

In this case, PT doesn’t stand for Physical Therapist like it usually does in things I write and across the medical spectrum. In this case, PT stands for prothrombin time (or “protime”) and INR stands for international normalized ratio. These factors combine to tell us many things about the effectiveness fo anticoagulant therapy. And, I’m sure you guessed it, they are important for us, as rehab clinicians, to do our best work for our patients. A normal INR in a patient who is not pharmacologically anticoagulated is 1.0. When we are pharmacologically anticoagulating, we want the INR to be between 2.0 and 3.0 and I have even been asked to go up to 3.5 for certain patients with multiple risk factors or who have mechanical heart valves. Average PT is 10-14 seconds.

IF you find that INR is greater than 5.0, you should NOT be performing any kind of therapeutic intervention and you should NOT be exercising the patient. Obviously, they will need to move enough to access care, and they should do so safely, maybe even with your help to prevent falls, but outside of that, they are inappropriate for therapy. If you find an INR higher than 6.0, the patients needs to get immediate medical attention as they are at an unsafe risk of bleeding. If you find the INR is too low, mobilization helps with blood flow which decreases clotting, so you should be working to mobilize the patient as much as you can in the absence of signs and sympyoms of DVT or PEs. However, you will still need to contact the physician as the patient may need adjustments in their anticoagulant dosage.

Doing this is actually really easy. We use a small meter called a CoaguCheck. Some patients have their own but I carried one regularly because I did so many of these. A small finger prick is done with clean technique, a capillary chip is inserted in to the machine, the blood is placed on the capillary chip, and a reading appears. There are several more pieces to this because the machines can be VERY finicky. The biggest issue is usually getting blood! I’ve put some serious time in to managing an arm from proximal to distal in an effort to “milk” blood to the finger to make sure I can get enough.

The best tip I ever received in performing this procedure is that you need enough blood to make it looks like a lady bug is sitting on the finger. This needs to be significantly more blood than what is required for blood glucose monitoring. I know that doesn’t sound like a lot, but if that blood is not therapeutically coagulated, it can be really difficult to get that much in the amount of time you are given. That’s the other hard part, the machine gives you a countdown in which you must apply the blood to the capillary chip. If you run the timer down, you have to start over with a new finger prick, new chip, and new reading.

I typically go at this in a specific way each time: getting everything set up with clean technique, then get the chip, machine, and lancet ready. I then start my timer (which happens when you insert the capillary chip in to the meter) and spend about half the time (90 seconds) working the arm, hand, and finger to make sure I am going to get enough blood. Then I clean the finger, lance it, and “milk” enough blood out to look like a lady bug is sitting on the finger. Finally, I apply the capillary chip to the blood, allow capillary action to do its thing, and then wait for my reading.

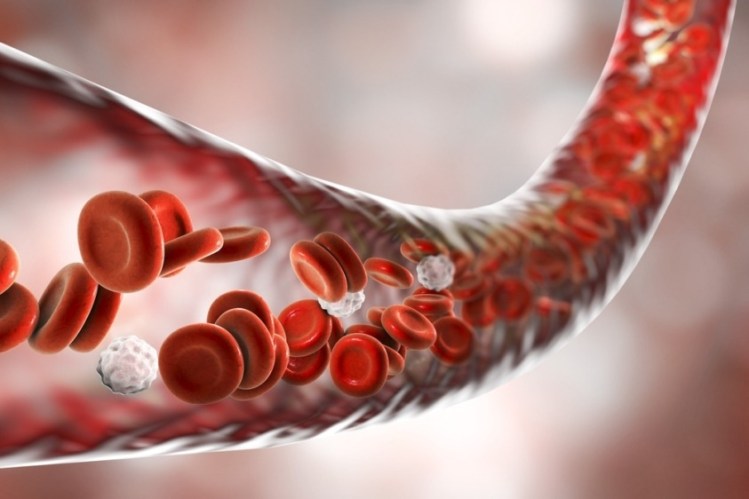

Especially after a surgery, many of our patients are on prohpylactic anticoagulant therapies to reduce their risk of developing blood clots that could be potentially fatal if they travel throughout the circulatory system and relocate themselves in the lungs. But post-operative patients are not the only ones I help with this minor technique. As many of you know, I manage many patients with complex chronic diseases that require them to be heavily anticoagulated. These conditions may include heart failure with atrial fibrillation, cancer when chemo effects to the heart, or they have hypertension, diabetes, and Factor V Leiden deficiency. There are a million combinations I could list here. Regardless, most of them end up on Coumadin/Warfarin for anticoagulation which means their PT/INRs have to be monitored for therapeutic effect.

Now, of course there are other options for long term anticoagulation, such a rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis). These have some serious benefits like not having your finger pricked weekly to monitor your PT/INR, not having to worry about dietary choices (see below), and having fewer drug-to-drug interactions. However, when you have a patient with a history or high risk of falls, you don’t really want them on these particular options. Even though the effects wear off sooner, once the anticoagulant is in effect, it cannot be reversed. Once you start bleeding, you keep bleeding. That’s a real concern when you develop a subdural hematoma from a fall.

Another drug in this “new” class of anticoagulants is Dabigatran (Pradaxa). I listed this one separately because a clotting antidote has actually been developed called idarucizumab (PraxBind). However, Pradaxa can still be hard on kidney function and tends to be incompatible with mechanical heart valves, similar to the other drugs in the “new” class of anticoagulants.

Things to watch out for when you have a patient utilizing Coumadin/Warfarin (outside of the obvious bruising/bleeding) include:

- Medication Interactions. All generally administered medications included

- Products containing acetaminophen

- Most broad spectrum antibiotics

- Aspirin

- all other NSAIDs

- Most antacids and laxatives

- Antifungals

- Amiodarone (or other rhythm drugs)

- Supplements. Just don’t. There are many interactions with various supplements and they are not well controlled or easy to treat.

- Foods. Anything high in Vitamin K. This means all leafy green and dark purple vegetables and fruits. This also means green tea. Like I mentioned above, Vitamin K is the antidote to Coumadin bleeding, so eating foods with higher levels of vitamin K will decrease the effectiveness of the drug.

- Other foods include grapefruit, cranberry, garlic, and black licorice

- Alcohol. Alcohol is also a blood thinner so you don’t want to double down on the effects of the medications.

Also, be on the lookout for bleeding that isn’t obvious. This can be GI bleeding, subdermal bleeding, internal bleeding, or cranial bleeding which would result in:

black or coffee-grounds stool or vomit

bleeding of the gums when brushing teeth (not otherwise explained)

severe head aches or stomach aches

dizziness, weakness, fatigue

low HgB and low Hct on CBCs

shortness of breath with minimal activity or at rest

new onset or increase in falls

ecchymosis of an entire limb or quadrant

All of these things would warrant immediate evaluation by a medical physician, probably in urgent care or emergency depending on the severity. Patients may need to receive the Coumadin antidote, Vitamin K or PCC.

Other considerations include the need for dietary support. Call in a consult to your dietician because these folks aren’t going to be able to eat much from a large class of foods that would otherwise be REALLY good for them. It’s not that people who take Coumadin/Warfarin CAN’T have foods with vitamin K, but they have to eat about the same amount every day to keep the blood levels steady. Spikes in the amount of Vitamin K people eat are what causes problems with their anticoagulation therapy. And, given we are basically asking people to limit a large category of foods that are otherwise REALLY healthy, people who take Coumadin/Warfarin are going to need some serious dietary support to avoid adding obesity to their list of medical conditions.

So, who’s up for picking some fingers? It’s a great easy may to help patient’s manage their chronic conditions in the home, on the go, or in a short amount of time. Expanding your role and fulfilling your scope is only going to help your patients be their best selves and make their best choices.

How about you? Do you do anything in your practice that is something you learned on the job but not otherwise part of your standard professional practice? Tell me about it in the comments!

References:

Collins, S. & Beckerman, J. (2016). How Do New Blood Thinners Compare to Warfarin? Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/atrial-fibrillation/features/warfarin-new-blood-thinners

Mayo Clinic. (2020). Prothrombin time test. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/prothrombin-time/about/pac-20384661#:~:text=In%20healthy%20people%20an%20INR,in%20the%20leg%20or%20lung.

Wax, E., Zieve, D., Conaway, B. (2019). Vitamin K. Medline. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002407.htm

Follow @DoctorBthePT on Twitter for regular updates!