I spent some really great times as an educator in a heart and lung transplant program at a large hospital system. Specifically, I was a therapy educator. I taught PTs, PTAs, OTs, COTAs, and SLPs what they needed to know to safely provide rehab to patient after heart and lung transplants. I saw so many of these patients both at our hospital and at their homes and helped transition them to cardiac and/or pulmonary rehab programs when they were ready. I loved working with this population! I mostly enjoyed the complexity of this type of case. Most of the time, they had a long course of illness prior to transplant. Some of them I even had the honor of pre-habbing prior to transplant and it was great to see them make that transition. After transplant, they felt like a new person!

But regularly seeing patients after transplant means knowing a specific set of symptoms to look out for because you have to be constantly monitoring for rejection. We will talk much more about transplants in another post but, some of those symptoms include:

- Resting Heart Rate less than 60 bpm

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Malaise

- A feeling of chest pressure

- Dry cough

- Decreased exercise or activity tolerance

- A decrease in lung function of 10% or more

Let’s take a closer look at that last one. How can we know if someone’s lung function has decreased by 10%? Well, you have to look at a measure of lung function. The one we used was FEV1, or forced exploratory volume in 1 second. This is the percentage of air you are able to forcibly exhale from your lungs in 1 second, after taking a maximal inspiration, and in comparison to your predicted ability. This may seem like a strange measurement, especially since it’s different for everyone and based on several factors, like your gender, but let’s break it down and you’ll see why it’s so important.

If you remember how lung volume works as I described in my video in dynamic hyperinflation, after you take a deep breath in, you have to get all that air out. And if you have an obstructive disease, you have to get even more out than what you put in. So the strength of your diaphragm begins to become a significant factor in your lung function. Therefore, FEV1 is a significant diagnostic factor for obstructive and restrictive lung disease. This also continues to be true after transplant. These patients are typically working with a weakened diaphragm from whatever disease state they experienced prior to transplant. As they rehab and heal, we expect their diaphragm strength to increase and their forced exploratory volume to increase. They no longer have trapped air to fight against because their brand new lung doesn’t (hopefully) have disease.

| GOLD stage of COPD | Percentage of predicted FEV1 value |

| Mild | 80 percent or above (in the presence of known disease) |

| Moderate | 50 to 79 percent |

| Severe | 30 to 49 percent |

| Very severe | 29 percent or less |

Everyone has a residual volume that just hangs out in the lungs so that part is normal. If your patient has a lung disease and they were able to get all our air out of their lungs in 1 second, then they probably didn’t have that much air in their lungs to begin with which would signal poor inspiratory volume, so we are targeting greater than 80%. Some healthy people can even get as high as 120% of their predicted value! Remember, this isn’t a percentage of the volume you have its a percentage of the expected volume you can exhale.

That’s all fine and good, but how the heck do we measure something like that without PFTs (pulmonary function tests)? One of the cool things our hospital did was utilize a device that went home with the patient to regularly measure lung function. It actually did a whole bunch of other things, too, like record and remind them about their medications. If you’ve ever seen someone after transplant, you know they have a ton of medications that have to be taken a thousand times every day. It was called a Spiro PD.

As cool as this device was, it was incredibly difficult to use properly and patients tended to get measurements that were all over the map. I found that they needed to be properly trained in how to take a deep breath and perform an FEV1 test with their new lungs! So here are some tips to generally improve FEV1 and overall lung function. You probably already do some of these things and just don’t know it!

- Stand up. This allows you to utilize your full lung volume better, all other factors being normal. If you are sitting, several postural factors can influence your ability to take a deep breath. This particular portion can become problematic if your patient has balance impairments, but they can always hold on to a hemi-bar, counter top, or their walker. Make sure they aren’t weight-bearing through their hands on whatever surface you are using because this facilitates accessory muscles. A maximal inspiration typically requires some trunk movement in to the posterior space, so be sure to guard them closely. Don’t make the gait belt too tight or you will impact their inspiratory volume.

- Use a mirror. Patients sometimes have no idea what they are doing when they breathe. Honestly, who pays attention to that, anyway? We jus breathe and get on with things. But we all know that patients develop some pretty serious compensations when disease is present which results in them changing their breathing patterns to less efficient techniques. Putting them in front of a mirror and utilizing this visual feedback can be really helpful in remediating those inefficient patterns. If you are using a bathroom mirror, this also allow them to use the counter top for support as needed.

- Pre-training in diaphragmatic breathing. Especially if your patient has experienced a pulmonary disease, they will have the need for diaphragm retraining. However, this is not limited to patients in a disease state. Diaphragm training can be helpful for athletes, too. If you can trigger that diaphragm to engage at the proper moment and increase the strength of contraction, you can help your patient improve their inspiratory volume. We will talk about this in greater detail in a different post. I find tactile cues to be really helpful, though! Find things that really help them focus on breathing OUT!

- Be ready ahead of time. So many times, I would be using the SpiroPD to test my patient’s FEV1 and they would place it down on the table or counter or the seat of their walker and then have to go hunting for it when it was time to breathe out. This wasted so much of their energy and ability to forcefully exhale. If you are using a measurement device for FEV1 or other lung function measure testing, have it in the patient’s hand, ready to go during testing so they don’t waste any energy.

- Coaching. Spirometry testing isn’t easy and patients are quick to give up if they don’t know how long this is actually going to take. When doing an FEV1 test on the Spiro device, the device needs to calculate ALL the air the comes out, not just what comes out in 1 second. That means the patient has to keep blowing as long as they can, or as long as the machine needs them to. THIS IS SO HARD! They will need you to coach them in continuing the test as long as needed. It will feel uncomfortably long!

Something I love to do with patients who have a SpiroPD device is have them do their normal testing with all their altered posters and inefficient techniques while I was with them. We would review their results which were typically pretty awful (30-40%), then train them, reposition them, and retest them. This almost always showed significant improvement in their measures. (I love using the test-retest method to show improvement and the value of our interventions! I talk about that here, too!) And, if it didn’t, I knew something was actually wrong and I could confidently report to the transplant team.

Another thing we do is some magical math to look at lung function. We take FEV1 and divide it by FVC (forced vital capacity). We want this ratio to be pretty close to 1 to indicate healthy lung function. If you would like to calculate your predicted FVC, FEV1, or many other lung function measures, you can do that here or here! My predicted FEV1 is 3.56 liters! So I would need to do a spirometry test to see what percent of that I actually get and that would be my clinical value.

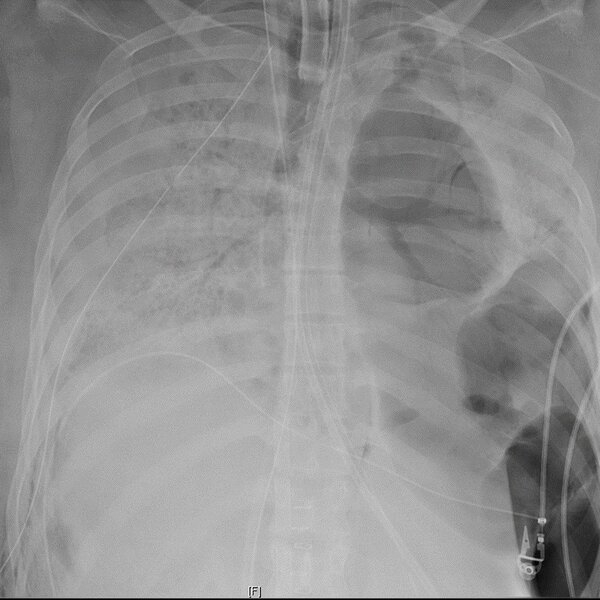

What got me on the track of talking about lung transplants? Well, I recently read an article about the first patient to receive a lung transplant due to COVID-19. A woman in her 20’s was admitted to the hospital for acute respiratory distress due to COVID-19. She had been on a ventilator for two months and was still failing. They transitioned her to ECMO, but she continued to decline. Her kidneys and liver started to fail and there was no hope of returning to normal. The damage to her lungs became irreversible. Doctors found that not only did she have a viral COVID-19 infection, but also ended up with bacterial abscesses in her lungs. After the viral infection had cleared, they determined the only way to save her was a double lung transplant. That picture above is her lungs prior to transplant. You can see that the left lung is nothing but giant air pockets and the right one is completely full of consolidation of varying types. All in all, nothing here is viable.

The next picture is of a lung removed from this twenty year old female. This lung is one of the most damaged I have seen. It’s like the lung tissue liquified. It’s hard to even describe. If you don’t want to see it, keep scrolling, but in case you do, here you go.

WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGE COMING UP NEXT

After transplant, this woman began to make a significant recovery. Her major organ systems began to heal and was working on coming off of ECMO while rehabbing. She did begin to show some of those signs of rejection we talked about earlier, but the anti-rejection medications seemed to be working well. She has a long road ahead of her fo many reasons. She was intubated and ventilated in the ICU for more than two months so she was significantly deconditioned. So what’s the overall outlook?

Well, patients who undergo lung transplant have about a 50% chance of surviving five years afterward. That number is improving slowly as the medical community gets better at interventions aimed at rejection, but her odds are still better than what they were prior to transplant where she had, at best, days before dying of multisystem failure. Her transplant candidacy was due to her very young age and lack of comorbid conditions, as well as her severe decline. I realize that, for those that are familiar with the transplant world, this could be somewhat controversial. People wait years for lungs and many never get them.

For those who are not familiar with the transplant system, this is not a go-to intervention. You have to have transplantable lungs available which means people have to be dying. You have to have a donor match. You have to have lungs that haven’t been infected with COVID-19. And you have to have a patient who is healthy enough (other than COVID-19) to receive the lungs. They also have to be generally the right size (although lungs can be resized to a point). Similar to ECMO, this is a literal last resort. This type of intervention takes a large team, including an extra set of team members from the transplant team, like social workers, transplant surgeons, specialized nurses and rehab providers, in addition to all the other wonderful medical professionals and family involved. The transplant team from Northwestern that perform the transplant on this women spent two and a half days just repairing the donor lungs she received to ensure they were the best quality for her.

What are some techniques you use to improve lung function? Tell me about them in the comments!

Follow my blog for more!

References

Herman, C. (2020). 1st-Known U.S. Lung Transplant For COVID-19 Patient Performed In Chicago. Shots: Health News from NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/06/12/875486356/first-known-u-s-lung-transplant-for-covid-19-patient-performed-in-chicago

LUNGFUNKTION — Practice compendium for semester 6. Department of Medical Sciences, Clinical Physiology, Academic Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. Retrieved 2010.

MedlinePlus. (2020). Transplant rejection. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000815.htm

Thompson, E. G., & Russo, E. T. (2019) Forced Expiratory Volume and Forced Vital Capacity. University of Michigan Medicine. https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/aa73564

Yeung, J. C., & Keshavjee, S. (2014). Overview of clinical lung transplantation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 4(1), a015628. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a015628

Follow @DoctorBthePT on Twitter for regular updates!

4 thoughts on “FEV1”