UPDATED!!!

This is the first half of a two-part installment on VTEs. Keep an eye out for part 2 on pulmonary embolisms (PEs) and how these are associated with COVID-19, coming soon!

If you work in outpatient therapy, this has probably been on your radar with just about every post-operative patient that comes through your door. If you work in home care or other sub-acute setting, you are seeing some pretty immobile people, and you consider this daily. And if you work in acute care, your radar is always scanning for these things, because you know that your patient is in the highest risk time-frame.

Just for clarification: VTE = Venous Thromboembolism (anywhere in the venous system) // DVT = Deep Vein Thrombosis (in the deep vasculature) // DIC = Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy

Let’s start at the beginning. What puts a patient at risk for having a DVT? The list is somewhat long:

- Prior history of DVT or PE

- Any recent history of surgery

- Active malignancy

- Immobility > 3 days

- Immobilized, weak, or paralyzed extremity

- Extended compression to an extremity

- Injury to a vein caused by fracture, trauma, or surgery

- Impaired circulation due to confinement, paralysis, or compression

- Increased estrogen due to medical therapies or pregnancy and up to 6 weeks after birth

- Chronic medical conditions including heart disease, lung disease, Cancer and cancer treatment, IBS/Crohn’s

- History of DVT, family history of DVT, obesity, Central Line, or inherited clotting disorders (Factor V/Leiden Deficiency is very common in Dutch blood lines)

You can download a system-specific symptom guideline here!

Source // For guidelines in app form, click here (iOS) or here (Android)!

How can you know if your patient has a DVT?

There are some standard criteria and special tests, like Homan’s sign, however, the sensitivity (~10%) and the specificity (~39%) does not make this a very reliable test for either ruling in or ruling out, so you can basically disregard it. Looking at the clinical picture is always your best bet, and using a standardized, evidence based tool.

- Swelling of an extremity or the face

- Pain in the affected area

- Tenderness to touch

- Redness of the skin

- Superficial venous protrusion

How do I prevent my patient from having a DVT if they are at risk?

- Promote mobility programs

- Promote anticoagulation adherence

- Graduated compression stockings

- Check clothing for wrinkles and tightness

- Educate patient on signs and symptoms

- Alternating pressure devices

- Ankle Pumps/Hand pumps if nothing else!

And to make life even easier, there’s an app for that! The Well’s DVT score that we utilize to determine a patient’s risk profile for developing a DVT has been converted to electronic format that you can download for your device.

You’ll notice, it also has a calculator for PE risk, we will get to that more in the second part of this post series. The Wells App is not the only one, it just happens to use a criteria that is widely recognized. There are other options that utilize similar criteria like the Caprini. Either way, you should get one of these free apps on your device so you can perform in-the-moment assessments of your patients.

One of the toughest things is that, if you look at the Well’s score criteria, you will see that pretty much any and every total joint replacement patient is automatically at high risk. This is actually 100% true! We know this and this is the reason we educate patients regarding signs and symptoms of DVT, so they can be on the lookout for complications when we are not there to help them! However, that doesn’t mean you need to call the physician. Like I said above, you have to correlate clinically. If their Well’s score is high risk AND they’ve had a significant functional decline AND they have an extremity that is three times the size of the contralateral one, then you should probably be making a call.

Education

Patients get pretty worked up about risks after surgery and need a good amount of post-operative education and education reinforcement to help them make appropriate decisions about the possible presence of a DVT, so you want to make sure they know what to look for. One of my favorite things to tell them is how to differentiate between post-operative edema and DVT-related venous pooling is that the affected extremity (which MAY NOT BE THE OPERATIVE ONE!!!) will be two to three times the size of the other side, not just at the joint, but the entire extremity. This paints a pretty clear picture and the patient can actually be reassured that, because they do not look like this, they probably don’t have a DVT to worry about. However…

“…about 30–40% of cases go unnoticed, since they don’t have typical symptoms”

NIH

So we have to continue to be vigilant. We have the opportunity to see patients far more often in the sub-acute setting, especially home health care, than most other providers, so we have to have eyes on and communicate with our team.

In my practice, I have identified several DVTs. The photo above of the positive DVT on the post-operative total knee arthroplasty was a patient of mine. My PTA saw this patient the day prior and called me to report something being wrong with his presentation. She asked me to see him for follow up first thing in the morning. At the time, he didn’t have the edema he has in the photograph. But it shows you that less than 24 hours can make a significant difference just in the physical appearance. He also had several other symptoms including confusion and a decreased functional status.

I have also identified DVTs in patients who were not post-operative, but were immobilized due to cancer treatment. It is important to keep in mind that, due to the cognitive symptoms patients can experience, even patients who are familiar with medical complications (such as doctors and nurses) can also experience DVTs if the conditions are right. So trust your clinical judgement, your gestalt feeling, and your evidence-based tools. Yes, I sent a doctor to the emergency department because I thought he had a DVT. He did. Like the ASH states:

“Blood clots do not

ASH, 2018

discriminate by age,

gender, or race. They

can affect ANYONE.”

COVID-19 and DVTs?

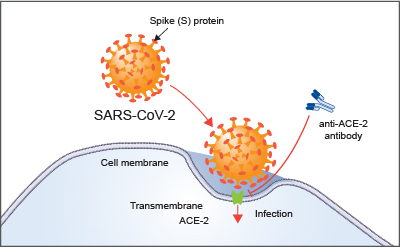

We know that patients with COVID-19 are definitely at higher risk for several reasons and through interference of several mechanisms (we talk about this here). Many of them are immobilized long term, whether in the hospital or at home self-isolating. A higher percentage of patients with COVID-19 have comorbidities like heart failure or diabetes that increase their general risk for DVTs. Newer studies are finding that the risk of DVT in patients with COVID-19 is about 20%. This strange thing called “blood stasis” in the femoral veins, which can lead to DVTs, is found in 70% of patients with COVID-19. That can be compared with the rate of DVT after joint replacement, which is about 0.15% for hip and 0.22% for knee – a massive difference.

And we also know that there may be an indirect mechanism by which this clotting occurs. When the endothelium is infected with COVID-19 and damaged, this triggers the clotting cascade, but this happens on a much larger scale than only a single point of compression or vascular insult. When the endothelium is damaged, it is damaged everywhere in the body that the viral RNA has infected it. When the patient has gone septic, that could be anywhere and everywhere. We talked about this in the post about how COVID-19 is recently becoming associated with increased risk fo CVAs.

Let’s also not forget that this risk persists long after discharge. We don’t know how long the risk persists. As long as the patient is recovering from COVID-19, whether it be in a rehab center or otherwise recovering with home-based therapy services, they continue to be at risk of developing a DVT or PE. According the ASH, 33% of people who have had a DVT will have another in less than 10 years time.

If you are already aware that your patient has a DVT, you are not technically excluded from exercising them. Let me be clear: if a patient has a NEW ONSET, acute DVT, you need to report this to the physician and get assessment and treatment immediately as risk of PE is very high. However, in patients who have acute DVTs under anticoagulation therapy or chronic DVTs (yes, these people are out there and you have probably seen them and not known it), you should be exercising them. According to the research, there is no increased risk for PE with exercise as compared to bed rest. Types of exercise included early mobility (household level) and ambulation, all the way up to vigorous treadmill programs (which actually showed fantastic long term results). If you think about it, these people are getting up and going to the bathroom and getting food aren’t they? So if household mobility does not increase risk, why would your interventions? Exercise should be implemented as soon as therapeutic levels of anticoagulation have been achieved.

You can review the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Physical Therapists in the Treatment of Patients with VTE:

Be sure to keep checking back for VTE Part 2: PEs! We will discuss how PEs are associated with COVID-19 and what you need to know as a rehab clinician.

What parts of the VTE CPG do you find surprising? What parts do you regularly implement in your practice? Let me know in the comments!

More Reads…

Pressure… Pushing Down On Me…

Breathing. I can’t stress it enough. If you’re not breathing, you’re dead… or in a lot of pain… either way, it’s not good. So breathe! In my practice, I work with a lot of different types of patients with a wide variety of conditions and comorbidities, but they all have one thing in common: they…

Dehydration

WHILE WE WAIT FOR THE NECT CHAPTER OF DIABETES MANAGEMENT, LET’S KEEP TALKING ABOUT INCONTINENCE

Chronic management of urinary incontinence can lead to many issues like infection and hospitalization if it doesn’t account for fluid balance! Let’s talk I’s and O’s! #physicaltherapy #incontinence #chronicdisease

Chronic Disease Part 3: Urinary Incontinence – Part 1

NEXT FEATURE IN THE CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT SERIES!!!

Let’s learn how to manage incontinence! But wait, that’s not a chronic disease, is it? Well, let’s take a look and find out!

Follow my blog for more!

Follow @DoctorBthePT on Twitter for regular updates!

References:

American Society of Hematology. (2018) ASH Clinical Practice Guidelines on Venous Thromboembolism. Retrieved from https://www.hematology.org/education/clinicians/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-practice-guidelines/venous-thromboembolism-guidelines on May 14, 2020.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020) Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/facts.html on May 14, 2020.

Hillegass, E., Puthoff, M., Frese, E. M., Thigpen, M., Sobush, D. C., & Auten, B. (2016). Role of physical therapists in the management of individuals at risk for or diagnosed with venous thromboembolism: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Physical therapy, 96(2), 143-166.

Kahn, S. R., Shrier, I., Kearon, C. (2008) Physical activity in patients with deep venous thrombosis: A systematic review. Thrombosis Research. 122(6): 763-773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2007.10.011

Kerbikov, O. B., Orekhov, P. Y., Borskaya, E. N., and Nosenko, N. S. (2020) High incidene of venous thrombosis in patients with moderstae to severe COVID-19. medRxiv [Published ahead of review]. Retrieved from https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.12.20129536v1.full.pdf

Lee, S. Y., Ro, d., Chung, C. Y., Lee, K. M., Kwon, S. S., Sung, K. H., & Park, M. S. (2015). Incidence of deep vein thrombosis after major lower limb orthopedic surgery: analysis of a nationwide claim registry. Yonsei medical journal, 56(1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.1.139

Streiff, M.B., Agnelli, G., Connors, J.M. et al. (2016) Guidance for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis 41, 32–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-015-1317-0