This post is written for one and all. If you are not a rehabilitation or medical professional, please read this post. Even if you are, please read this post. I’m going to address some things that need clarification. You can have all the opinions you would like, but there are some things that are just facts. Not opinions, not choices, not beliefs. Facts will continue to exist whether or not you believe in them. Facts can and do change contextually and over time, but not based on someone’s opinion of them. They change in response to a change in evidence, science, and environment.

Today I’m going to provide you with some old evidence and old science. The reason for that is two-fold. First, it’s because masks are OLD! We’ve been using them for a long time. The second is because I didn’t want to use any single bit of research that was influenced by the environment of COVID-19. The world view of science has become terribly distorted in the last year so I’ve only used research from before the time of “alternative facts” and just used facts. Keeping it simple.

The other day, I met a young woman who described herself as, “someone other people don’t like,” because she doesn’t wear a mask. She then said that even when she worked in the hospital, she just “didn’t like” wearing them. She then attempted to get me to agree with her that, “well, you work in healthcare, you know they don’t work. They stop droplets but they don’t stop the virus.” She then told me that 30 of her friends have COVID-19 from a large camping trip and are very sick and that she wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

Let me make this perfectly plain:

MASKS WORK.

- They work best when used in conjunction with other methods of infection control.

- Different types of masks work to different levels and nothing is perfect. Not all masks, and not even all surgical masks, are created equally.

- Masks that are not worn properly work less.

This person I met who “worked in a hospital” is spreading fallacies and doesn’t understanding virology, infection control, or public health concepts. She is also terribly confused based on her story of her friends’ illnesses. I’ve heard so many arguments against masks by people from all walks, medical or not, science or not, government or not. But here are the facts:

- Medical Providers have been wearing facemasks regularly since the 1960s because they reduce the rate of infection transmission to others.

MacIntyre, CR; Chughtai, AA (9 April 2015). “Facemasks for the prevention of infection in healthcare and community settings”. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 350: h694. doi:10.1136/bmj.h694. PMID 25858901. - And before you start in on cloth vs medical/surgical masks, even cloth masks have been used around the world since 1897 to reduce the spread of infection. They were actually surprisingly successful at reducing diphtheria infections (by 78%) and completely eradicating scarlet fever infections among nurses. And this was only a 2-layer gauze mask! A 6-layer cloth mask actually reduced tuberculosis infections among nurses by 50%! This is a big deal because Tuberculosis is airborne and highly virulent.

Chughtai, A. A., Seale, H., MacIntyre, C. R. (2013). Use of cloth masks in the practice of infection control – evidence and policy gaps. International Journal of Infection Control. 3(9):1-2. Retrieved from https://www.ijic.info/article/view/11366/8308 - Six new research articles have come out that unequivocally side with the use of masks to reduce spread of COVID-19. We didn’t have the evidence before, but we have it now.

- Performance of Fabrics for Home-Made Masks Against the Spread of Respiratory Infections Through Droplets: A Quantitative Mechanistic Study

- Quantifying Respiratory Airborne Particle Dispersion Control Through Improvised Reusable Masks

- Who is wearing a mask? Gender-, age-, and location-related differences during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Face mask wearing rate predicts country’s COVID-19 death rates: with supplementary state-by-state data in the United States

- Causal Impact of Masks, Policies, Behavior on Early Covid-19 Pandemic in the U.S.

- Could masks curtail the post-lockdown resurgence of COVID-19 in the US?

How and Why do Masks Work?

To answer that, we have to discuss the Chain of Infection. There are 6 links, which are pictured below. At any point, we as humans can insert ourselves or our interventions in to the chain to reduce or stop the infection risk.

Step 1: You can’t get sick if there isn’t a microbe around to get you sick. This is where engineering controls can really make a difference. Proper ventilation, cleaning, and other engineering controls remove infectious agents and, therefore, remove the risk of infection.

Step 2: You have to have an infectious source. This would be the person who is infected. This person, if they were aware that they were sick or contagious, could stay home and away from others, not sharing what they have and then the infection dies without being passed to another person. Antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, and antiparasitics can also intervene here. Kill the infectious agent in the host so it can’t spread.

Step 3: The microbe has to exit the person who is sick. Some viruses have very specific ways they can leave the body, such as only through certain bodily fluids. HIV is one of these viruses. Many body fluids do not serve as a means of exit for HIV, only certain ones (blood, etc.). In conditions like tuberculosis, the microbes are spread in the air by the infected person breathing (respiratory droplet nuclei). The infected person would likely have a hard time keeping a respiratory microbe inside their body and they symptoms typically produce coughs or sneezes, so engineering controls can be helpful here again, OR the person can block the exits of their body by using a mask to prevent the spread of microbes to others. Some microbes that don’t require respiratory transmission, like sexually transmitted viruses, are blocked by other barrier devices.

Step 4. The microbe has to have a means of contact to another person. It can’t just be any contact, it has to be the specific type of contact that the microbe requires. The microbes on your hands have to get to your eyes, nose, mouth, or whatever they can infect. If you utilize interventions such as washing your hands, that may never happen. Some microbes linger in the air (like we discussed above with tuberculosis) and have to be breathed in. This is also where barrier devices are useful. You can wear a barrier device to protect yourself.

Step 5. Once the microbe has made contact, it must access the type of tissue in your body it is able to infect. So, just because you became that person in step 4 who had contact with droplets on your hands, doesn’t mean you’ll contract an illness, unless your then put your hands in your mouth or rub your nose. Once this happens, the microbes have entered your body. There are a few things that can prevent this from happening including PPE. Healthcare workers know we are going to make it through step 4 on a daily basis, so we wear gloves, gowns, shields, and other pieces of equipment to ensure that the droplets that do land on us can’t cause infections. We throw all that stuff away so the droplets don’t contact any part of us.

Step 6: Once the microbe has entered the body, the immune system goes to work. But if the immune system isn’t strong enough for any reason, it will become easily overwhelmed. This doesn’t necessarily have to be a weakened immune system, either. Sometimes, microbes are able to overwhelm even healthy immune systems. That’s why even healthy people get sick sometimes. Some microbes are just really good at what they do. People who do have weakened immune systems sometimes take antibiotics every day to help fight off infections that find a way in.

Specific to COVID-19…

In the specific case of COVID-19, the virus can’t magically travel from person to person on its own. As a respiratory pathogen, it has to be carried on droplets or droplet nuclei that are breathed out, coughed out, sneezed out or spit out in one way or another (these are called “aerosol generating procedures“). The spread of both droplets and droplet nuclei are significantly reduced by a mask. Because people may not know they are infected, we automatically skip to step 3 in the chain of infection. Once the virus exits the body of the carrier by one of these methods, it is transmitted to those around them. Masks then reduce the ability of someone else’s droplets to land in your nose or mouth because they are covered. This is why protection is a 2-way Street. If your mouth and nose are uncovered, my droplets have a higher chance of landing in your mouth and nose and your droplets have a higher probability of making it to me. Like I said, nothing is perfect, but the mask helps reduce the risk.

Something I see brought up often is that healthcare providers are wearing masks, but they still get sick. This is where we need to consider is viral load. The more people you come in contact with who have any viral illness, the higher your viral load. And remember, with COVID-19, the majority of people are asymptomatic carriers. But, we also know that with COVID-19, the more exposure to the virus, the more severe the disease presents. Wearing a mask significantly decreases your viral load, allowing your body to fight a smaller amount of virus so can remain healthy. It allows your immune system to do its job without being overwhelmed by the infection. So, yes, medical providers wear masks and still get sick. That is because we take on a much higher viral load, especially in the emergency care and ICU settings, because so many of the people medical providers come in contact with have COVID-19. You are in lesser contact in the community because those people aren’t showing that they are sick. Only patients showing symptoms, who are much more likely to carry disease, seek medical care.

Here is another example:

In the world of wound care, we have patients wash wounds with soap and water, or sometimes specific agents, to reduce the bacterial load on their wounds. If the wound is already infected, washing it reduces the work the body has to do to fight off the infection. In other words, it supports immune function. If the wound isn’t infected yet, reducing the bacterial load helps the wound not get infected because the immune system doesn’t get overwhelmed and can continue to do its job.

For more information about viral load, engineering controls, and different levels of infection control, please check out this post! PPE is the WORST!

But I can’t breathe in a mask!

If you know me, you probably know that I spent years working with people pre- and post-lung transplant who were at the end stage of lung disease. They were literally days away from suffocating to death. After transplant, they were on immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives. All of these people wore masks whenever they went out to protect themselves because one bout pneumonia from someone else’s droplets could kill them. One outing in too much pollen could land them on a ventilator. One day of their neighbor running a wood stove could mean a week in the hospital. I also work with people who have end-stage COPD, heart failure, pulmonary fibrosis, and all other manner of heart and lung diseases. These people are wearing masks every day while in our facilities to protect themselves. My incredibly sick or immunocompromised people can breathe just fine in their masks, even while I make them do therapy.

Schroedinger’s Mask

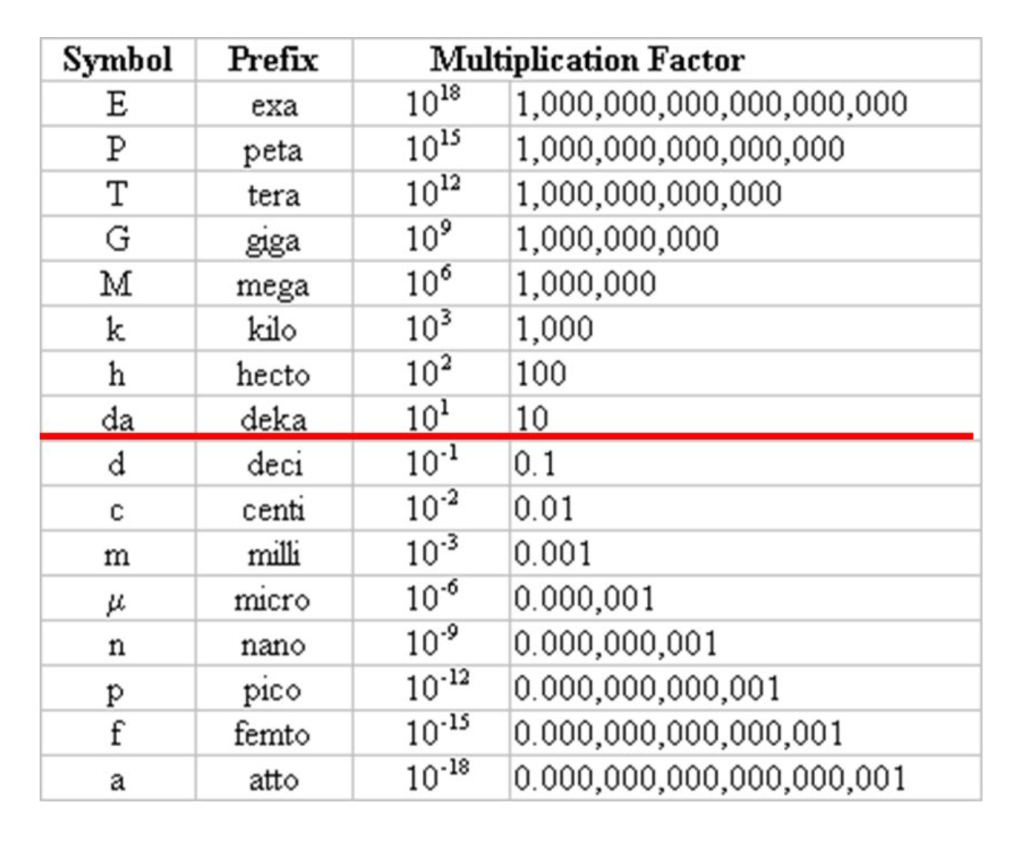

We need to understand that it is not possible for masks to be so effective at blocking air that people can’t breathe, while simultaneously being completely ineffective at blocking a virus. Like I said, even my very sick patients can still breathe while exercising in their masks! This is because surgical masks filter at about 5 micrometers (the average size of those droplets we talked about). Carbon dioxide (CO2) has a diameter of 116 picometers and Oxygen is 152 picometers so they are breezing through your mask without a problem. Surgical and cloth masks do not seal to your face, and provide ample room for oxygen and carbon dioxide to leave the breathing space. An N95 respirator filters at about 0.3 micrometers, or 300,000 picometers, so CO2 and oxygen flow right through those also. If you have high carbon dioxide content in your blood, you probably have an underlying lung disease (like my patients) and a mask won’t change this. Several physicians have taken their own and others’ arterial blood gases after a full shift of wearing an N95 to find that their PaCO2 (the amount of carbon dioxide in their blood) is completely normal.

For those not familiar with the comparison: 1 nanometer = 1000 picometers. Here is a chart:

SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has a diameter of 60-140 nanometers. That means that the SARS-CoV-2 virion is exponentially larger than a CO2 molecule, yet still small enough to get through even an N95. That doesn’t mean they can’t be filtered! Like I explained above, the virion can’t just magically move from person to person. It has to be carried on a droplet or droplet nuclei. Droplets are about 5 micrometers on average, which is why surgical masks filter at this rate. N95s filter at 0.3 micrometers because this is the average size of droplet nuclei. Yes, cloth masks are different, but still can block large droplets and significantly reduce all droplet spread so they don’t come in contact with other people (remember the links on the chain!).

For the medical folks…

There was a Cochrane review performed in 2014 regarding the effectiveness of surgical facemasks at preventing infection. This review showed that there was no statistically significant difference in infection rates between the masked and unmasked group in any of the trials when worn during surgical procedures. (WHAAATT?!?!) I know, but this review was discussed at length by several authors and there are some important things to point out, specifically that only 3 studies could even be included because NO ONE WANTS TO BE THAT SURGEON! One of the discussions had this to say:

“when current surgical practice is the culmination of layer upon layer of precautions in the hope of preventing surgical site infection, do we dare to experiment with their omission to see if they have any tangible consequence on morbidity and mortality? “

Da Zhou, et al. (2015)

Well, of course, someone dared…

A few randomized controlled trials attempted to remove any single step in the operative infection control process to terrible detriment of the patients. Many of the studies had to be stopped because so many people were getting sick that the studies could no longer continue. The overall picture is that surgeries are highly infection controlled: from the pre-operative antibiotics to the ventilation systems to the pre-surgical scrub-ins to the sterilization procedures, so what single piece of this process that contributes most to infection prevention is hard to know because they all work together. Just like infection control in the larger population, it requires more than one step.

What I’m trying to say is that you are going to have a very hard time explaining to me why you can’t wear a mask unless you are a child under 2 years old. My colleagues from 24 to 61 years old are running with masks on daily without oxygen desaturation. Medical providers (myself included) are working 8-12 hour shifts with masks on and not desaturating. We are moving and lifting equipment and human beings repeatedly while we wear them. Transplant surgeons wear their masks for 14 hours straight while swapping new lungs in to a human being. Does that mean we aren’t uncomfortable at times? No! Do we like wearing masks? No, absolutely not. But, like I tell everyone else, liking it is NOT a requirement.

“It is important not to construe an absence of evidence for effectiveness with evidence for the absence of effectiveness. While there is a lack of evidence supporting the effectiveness of facemasks, there is similarly a lack of evidence supporting their ineffectiveness.”

Da Zhou, et al. (2015)

To this day I have only heard of a few legitimate medical reasons to not wear a mask: 1. A patient had multiple facial and skull fractures from a car accident that caused extreme pain from the ear loops and an inability to get coverage of the nose and mouth. His Occupational Therapist found something else for him to wear instead.

2. Emotional trauma from abuse or neglect involving covering of the nose/face/mouth resulting in anxiety, panic attacks, or other mental health conditions.

Remember, I have worked with the sickest of the sick and those at the end stage of lung disease. These people have significant physical and mental trauma from being constantly in fear of suffocating to death at any moment. If they can wear a mask for three hours of medical appointments while on 14 liters of oxygen, then most people can wear them for a 15 minute trip to the grocery store. There may be a few other exceptions that I haven’t yet come to know, but for these few that have difficulty (not that they CAN’T wear a mask for a short time, it is just difficult for them), the rest of us have to do our part to break the chain for them by following the rest of the steps. We have to keep each other safe.

UPDATE as of September 1: I have yet to encounter any other examples were a mask would not be possible. Still waiting…

Got some ABGs you want to share? I’m all ears! Throw them in the comments!

Follow my blog for more!

References

Chughtai, A. A., Seale, H., MacIntyre, C. R. (2013). Use of cloth masks in the practice of infection control – evidence and policy gaps. International Journal of Infection Control. 3(9):1-2. Retrieved from https://www.ijic.info/article/view/11366/8308

Da Zhou, C., Sivathondan, P., & Handa, A. (2015). Unmasking the surgeons: the evidence base behind the use of facemasks in surgery. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(6), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815583167

Lipp, A. and Edwards, P. (2014). Disposable surgical face masks for preventing surgical wound infection in clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD002929.

MacIntyre, CR; Chughtai, AA (9 April 2015). “Facemasks for the prevention of infection in healthcare and community settings”. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 350: h694. doi:10.1136/bmj.h694. PMID 25858901.

Royal College of Nursing. (2016). The Chain of Infection. Retrieved from https://rcni.com/hosted-content/rcn/first-steps/chain-of-infection.

Follow @DoctorBthePT on Twitter for regular updates!

4 thoughts on “A Public Service Announcement: The Chain of Infection (and How YOU Can Break It!)”